Words: Cassandra Stern

Photos: Zac Stern

“The term ‘brick’ refers to small units of building material, often made from fired clay and secured with mortar, a bonding agent comprising of cement, sand, and water.” The brick is a classic, and arguably iconic building material, it is well-entrenched in American architecture. From the classic red clay to the stunning chromite grey, it is difficult to visit any urban area in the continental United States and fail to see even a single brick structure. From historic homes to modern skyscrapers, bricks are seemingly everywhere, and for good reason.

“Long a popular material, brick retains heat, with-stands corrosion, and resists fire…used as a building material for at least 5,000 years, currently the use of brick has remained steady, at around seven to nine billion a year [in the United States], down from the fifteen billion used annually during the early 1900s.”(http://www.madehow.com/Volume-1/Brick.html)

The long and colorful history of the brick traces back to the middle east, where sunbaked clay was plentiful and, while not very durable, certainly an abundant and useful construction material. After the Babylonians discovered that the brick could be hardened with high heat, the technology took root in human culture. After the collapse of the Roman Empire, the brick made a resurgence in popularity with the Dutch in the 1600s, which was carried over to North America with the tide of colonization. Prior to 1865, bricks were generally produced in small batches, but with the invention of the Hoffmann Kiln in Germany, technology finally allowed for commercial mass production.

Brickmaking improvements have continued into the 20th century, and as more efficient methods and technology have developed, today brick has “the largest share of the opaque materials market for commercial building [in the United States], and it continues to be used as a siding material in the housing industry.” So, how exactly does a blob of clay become the iconic brick that is a piece of the backbone of American architectural history? The process, with some refinements over the years, has remained relatively simple, straightforward, and increasingly efficient.

When stepping into brickwork to manufacture a quality product, the first step is to use a jaw crusher to pulverize the raw materials into smaller pieces, which are filtered by a separator machine. These organic materials include “natural clay minerals, including kaolin and shale, [which] make up the main body of brick.” These materials could also include various forms of sand to provide a coating of a certain color or texture upon firing. Additionally, “small amounts of manganese, barium, and other additives are blended with the clay to produce different shades, and barium carbonate is used to improve brick’s chemical resistance to the elements.”

Once the desired combination of ingredients has been mixed together, the batch is then moved onto processing, either by extrusion, molding, or pressing. Extruded bricks are “made by being forced through an opening in a steel die, with a very consistent size and shape,” while molded bricks are instead formed in individual molds, either by hand or machine. Pressed bricks, the least common of the three manufacturing methods, involves compressing the materials together with great force, resulting in a smooth and distinctive finish. Following the formation of the bricks, “they are dried to remove excess moisture that might otherwise cause cracking during the ensuing firing process,” and are placed into a kiln for firing. After being “burned”, or hardened at high temperatures, the bricks are removed and placed for cooling, before finally being

Historically a heavily laborious process when done by hand, technological advancements have completely revolutionized the efficiency of the dehacking process. “Automated setting machines have been developed that can set brick at rates of over 18,000 per hour and can rotate the brick 180 degrees. Usually set in rows eleven bricks wide, a stack is wrapped with steel bands and fitted with plastic strips that serve as corner protectors. The packaged brick is then shipped to the jobsite, where it is typically unloaded using boom trucks.” This increased efficiency has cemented the brick as a reliable and durable material that can potentially be produced quickly and can either be cost-effective construction, or a luxurious indulgence of higher cost and quality.

However, while bricks have been trusted and will continue to be trusted to keep our families and loved ones safe at work, school, home and more, the fact remains that even bricks, especially ones weathered by time and the elements, will not always last forever.

While modern brick manufacturers have worked diligently to develop new chemical additives and processes to extend the durability and longevity of brick, weather conditions and natural processes still, unfortunately, will wear the material down over time. One particular frustration to brick manufacturers is “efflorescence, which occurs when water dissolves certain elements (salt is among the most common) in exterior sources, mortar, or the brick itself. The residual deposits of soluble material produce a surface discoloration that can be worsened by improper cleaning. When salt deposits become insoluble, the efflorescence worsens, requiring extensive cleaning.”

Unfortunately, cleaning is not always the solution, and particularly with historical buildings, these failing bricks will eventually need to be completely replaced. At times, the original bricks can be salvaged by being carefully removed and replaced with fresh mortar, but often the original bricks are too worn or in too great a state of disrepair to be saved. When this unfortunate circumstance arises, building owners will turn to brick manufacturers and firms who specialize in restoration construction for brick matching and repair.

Nathan Karaway of Illinois Brick Company is one such expert. Serving the masonry community for over 15 years, Karaway has cultivated a wealth of knowledge and experience to become a formidable force in the industry and can provide a unique insight into the challenging process of matching bricks for a building repair or restoration. According to Karaway, the component that has made the biggest difference in the process has by far been technology. When detailing the process, Karaway described the incredibly cumbersome and inefficient steps that he used to undertake when taking on a brick restoration project.

First, he would need to commute to the physical jobsite, in order to inspect the bricks that would need replacing, get a sample, and then drive back to his office in order to manually pull and compare samples that might be a close match. This would compound in difficulty if, say, the bricks being restored were a more commonly found red clay with worn or indistinguishable identifying characteristics and composition.

After pulling anywhere from a few to a few dozen samples, or a master key panel from a major manufacturer, he would then need to physically return to the jobsite for comparison and a hopeful match- without one, he would then need to repeat the process until a match was achieved. In comparison, with the advent of the Internet Age, this process has been streamlined tremendously.

Now, to begin a job assessment, says Karaway, it’s as simple as performing a quick Google search to be able to begin the process of initiating a brick match. The Internet has also brought the brick community together, and now fellow manufacturers and firms can easily collaborate on projects and pool knowledge to better serve their consumers.

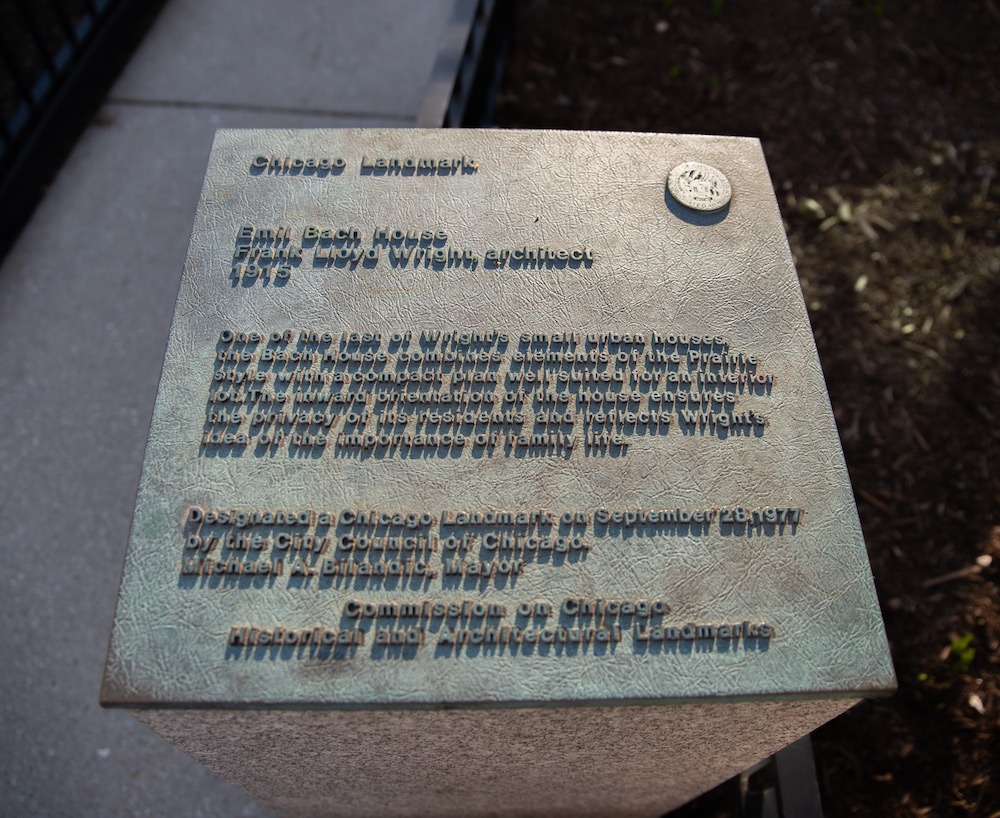

Additionally, when undertaking a restoration project, Karaway emphasizes the importance of selecting a partner who is well-equipped to handle the magnitude and scale of the job. For Karaway, one such project was the restoration of the historic landmark, the Emil Bach house in Rogers Park, Illinois. Designed by acclaimed architect, Frank Lloyd Wright, and constructed in 1915, “the Emil Bach House…is regarded as one of Frank Lloyd Wright’s last Prairie-style houses. Built for the brickmaker, Emil Bach, the house was designed with a very compact plan of under 2,000 square feet with three small bedrooms and a sun deck on the second floor…The significance of the Bach House is demonstrated by the fact that it was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1979 and named a City of Chicago Landmark in 1977.”

When Karaway set out to restore the Bach house, he knew he needed to immediately partner with a manufacturer who had the best reputation for working with historical buildings, and who had the means and facilities to be best equipped for the job’s unique needs. He reached out to Brian Belden of Belden Brick and Supply Company. Belden took the challenge in stride with Karaway, but they immediately ran into some difficulty. “The biggest issue for us was the brick was a unique size in comparison to today’s standard brick sizes,” says Belden. “The bricks were slightly longer and taller than a normal modular size brick, but smaller than some of today’s oversized units, so we had to make sure we had the proper tooling to make the appropriate size units.

The texture was also a non-stock texture,” continues Belden, and “we needed to make some trial samples for approval of the architect. We probably made, in total, three trials run of production for approval on the size and texture.” The project was time-consuming, with production and the approval process taking about six to eight months, and the overall project completion within a year.

In order to combat the challenges of replacing bricks “made in old beehive kilns” says Karaway, he and Belden ultimately invented a whole new brick for production. Belden says they began by getting “photos of the brick on the existing home, and we had actual samples from the job sent to our production team for reference.” Once they were able to analyze the actual brick samples in person, Belden could then understand “the dimension and spacing of the vertical texture, [which] required a custom fit of the texture device to the brick column during production.”

This proved to be tricky, explains Belden, because “if the spacing between the vertical scratch was too wide, the brick would not match, so we had to adapt our existing vertical scratch texturing device to meet the job needs.” Ultimately, Belden and Karaway’s efforts paid off in dividends when they were able to perfectly match the existing Bach brick, and restore the home to its formerly exquisite state. Despite the challenges, Karaway is happy the project was restored so beautifully and maintains while there was little publicity or profit tied to the work, “they did it because they wanted to help a customer, and they wanted to help a historical building.” This speaks volumes of the integrity and grit that it takes to achieve a successful outcome with such a complex project.

From interiors to exteriors, from fences to bookcases, bricks have always been and remain an integral fixture in the construction of homes, businesses, walkways and more. From the common red clay brick to the show-stopping black or grey, brick continues to resonate across the American countryside as a beautiful and functional architectural material. Now manufactured with greater efficiency and consistency than ever before, the performance and durability of brick has never been better, and although bricks, like any other material, can fail over time, advancements in the brick matching have streamlined the restoration process as a result. When speaking to industry leaders and examining a beautiful example of a successful restoration with the Emil Bach house, it is clear from the brick community’s passion and enthusiasm for their craft will continue to ensure the use of brick for the next 5,000 years to come.

References:

(http://www.madehow.com/Volume-1/Brick.html#ixzz5lJtri8bk)

(https://www.harboearch.com/bach-house.html)

(http://www.madehow.com/Volume-1/Brick.html#ixzz5lPVjxnL0)