The Role of the Cavity Space in Masonry Construction

By Jim Keene

Moisture is commonly known to cause problems in roofing and foundations, but it can also present major problems in masonry walls. Moisture intrusion occurs in walls as much as other places, and stopping the liquid water and managing it are important above-grade just as in a below-grade application, only with vapor drive playing an essential role too.

Now there are some very complicated debates in wall design. Some of them are extremely sophisticated, such as the selection of whether to use an air barrier, a vapor barrier or a weather barrier in the wall. Even more important is how these products will be selected and placed in the wall. Our expertise is at a more simple function — we make materials that relieve hydrostatic pressure above- and below-grade. We just want to make sure that everyone recognizes that the masonry cavity is an important part of the wall and that it drains properly. There are a variety of different ways to achieve this.

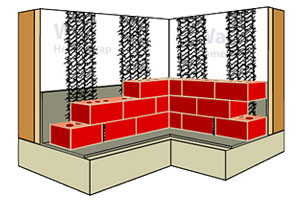

When a mason builds a brick wall with a two-inch cavity, the greatest concern is the accumulation of mortar within the wall. As the wall is built, the mortar is not struck off in the back of the wall. When the brick is pressed into place, the excess mortar clings to the back of the brick and can fall to the bottom of the wall, clogging weep holes. In effect, the most important aspect of the solution is to handle the mortar and assure the droppings do not cause a clog — hence a mortar collection device. This is a very straightforward solution for our typical commercial construction.

Unfortunately, that two-inch cavity is rarely used in residential housing construction — often diminished to one-inch thick — or, when it is used, the two inches of airspace are filled with an inch of insulation. Worse yet, many residential buildings have no sizable cavity and a half-inch space between the brick and the interior weather barrier is standard. Also, residential jobs typically have no flashing or weep holes.

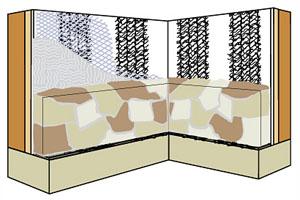

In cavities of one inch or less, the mortar often does not fall to the bottom of the cavity, but instead can become stuck between the masonry veneer and the inner wall, causing a bridge. Although clogging of the weep vent is less likely, it does present other problems in the form of blockages, which impedes ventilation and draining. The mortar that is oozing out the back and clinging to the interior wall creates a shelf for moisture to sit on and places surfactant-laden mortar in direct contact with surfactant vulnerable weather barriers.

Depending on the length of the wall the mason is building and the set time of the mortar, he or she may unknowingly create a series of dam-like mortar buildups at different points above the flashing line. A mason installing a 20-foot section may return to the next course to find a hardened mortar dam on the course below. Any mortar that does not cling to the inner wall behind the newly laid brick will ultimately cling to the already hardened mortar on the previous courses, creating even bigger blockages.

The major concern of an inch or less cavity wall is the drainage of moisture and the efficiency of ventilation. If we can keep the air moving and the mortar dams to a minimum, we can keep the potential for water passing back to a minimum. These once again are residential projects, and the sophistication of the system has to match the budget of the builder.

In a thin cavity, the priority is to create a space with a drainage plane throughout the wall, such as with a rain screen system or use a common technique in below-grade and create "chimney" drains matched to the weep holes. The chimney drain will provide a positive drainage path for liquid moisture to move freely to the weep, while also disconnecting the mortar dam that will occur so that air movement is assured throughout the cavity. The chimney system will not prevent the touching of mortar to the inner wall, but this is a matter of economic solution more than anything.

Filter cloths have been suggested as the drainage medium in a brick cavity, in lieu of normal weep vents and a drainage device. However, fabrics clog over time and the drying of the wall is just as, if not more important, than drainage. Fabrics have very low levels of air penetration especially when a 10-foot wall of brick sits on top of them. A minimum of 1/4 inch is necessary for convection (movement of air) to be sufficient for drying to occur, and a fabric can let liquid moisture out but is insufficient for air movement. Some parts of North America require a greater space for air movement, such as in Western Canada and the Pacific Northwest, where between 1/2 inch and 3/4 inch is required by building codes.

In order for any of these systems to work, we have to have a plane for moisture to drain. A weather barrier, building wrap or an air barrier will suffice for this. All of these systems expect that the wall will have a moisture impermeable plane on the inside of the inner wall (block back-up wall or sheathing in a veneer) on which moisture can flow unobstructed to the bottom. Whether this is primarily an air barrier, vapor barrier or weather barrier is debatable. The moisture must be able to follow the path to the bottom of the wall. All of this, however, is a moot point if proper flashing is not installed.

Stone should have a cavity behind it in order to prevent moisture from getting to the inner wall. I've seen instances where stone is fully grouted to an above-grade, wood frame structure — this is a sure way to create mold and to have permanent moisture problems. Stone walls should have a cavity wall design and mechanical ties to the inner wall; also, the cavity should be clean.

Thin stone and manufactured stone both let moisture through and have a significant quantity of mortar joints for even greater moisture intrusion. Neither system usually provides an opportunity for a typical one-inch minimum cavity. One solution in this application is to install a full-wall rain screen behind the scratch coat and expanded metal lathe. Once again, the minimum rain screen thickness should be sufficient to allow for convection drying of the inner wall and the system must have a weather, vapor or air barrier plane for moisture to drain to the bottom of the cavity. Weep holes are also an essential element in this application.

Ultimately mortar buildups between the masonry wall and the inner wall are, in themselves, not the problems, but rather the poor ventilation and drainage they create. By installing a masonry drainage device that allows for proper drainage and ventilation, despite the presence of mortar buildup, we can eliminate the damage without the costly and time-consuming techniques of trying to eliminate mortar buildup.

About the Author

Jim Keene is President of Keene Building Products.