The three-part rule for moisture management

Get moisture off of, out of and away from a construction detail as quickly as possible

By John Koester

The three-part rule of moisture management is to “get moisture off of, out of and away from a construction detail as quickly as possible.” However, we are left with the nagging questions: Off to where? Out to where? Away to where?

Answering these three questions is the really difficult part of the rule. Only a fraction of the liquid water involved will evaporate into thin air and, in some cases, even then it still can have a negative impact on the construction detail.

Part I: Off a construction detail

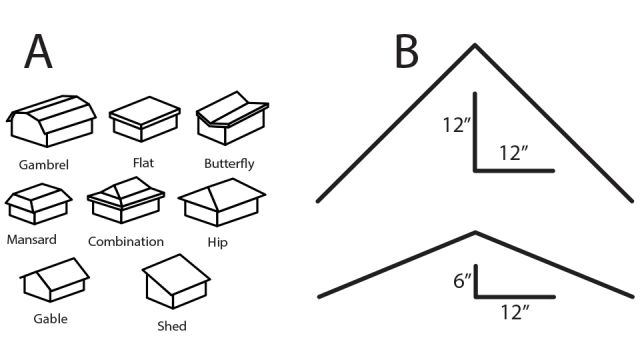

Let’s start with getting the water “off of” a construction detail. Obviously, this applies to hundreds and hundreds of details; however, let’s start with roofs. Roofs can be sloped to drain in many directions. (See Image A.)The roof style depends on numerous factors, including architectural style, distance to be covered, budget, etc. Generally, for moisture management purposes, the more slope, the better. The greater the slope (pitch) on a roof, the faster liquid water can run off. (See Image B.)

This is important, since the less time liquid water is on a construction detail (roof), the less likelihood it will absorb into that construction detail.

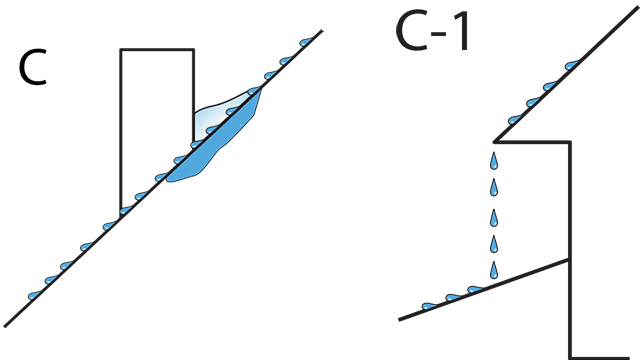

We also should reduce the number of projections or obstructions that are in the path of this draining liquid water. Anything that slows the flow of liquid water off a construction detail, such as chimneys or vent stacks, increases the amount of time that liquid water will spend on the construction detail. (See Image C.)

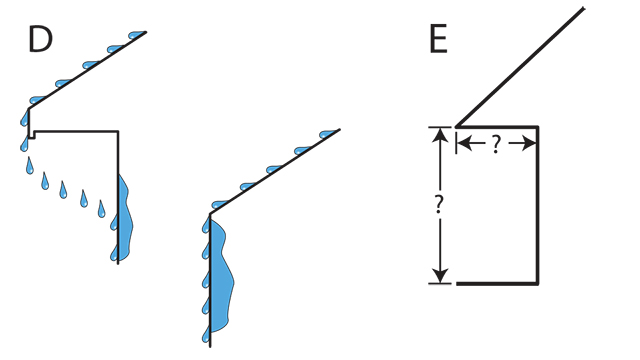

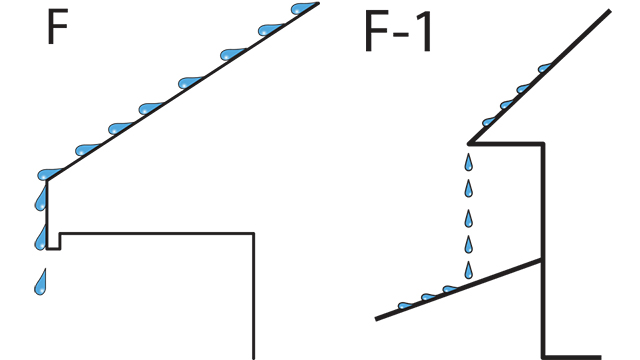

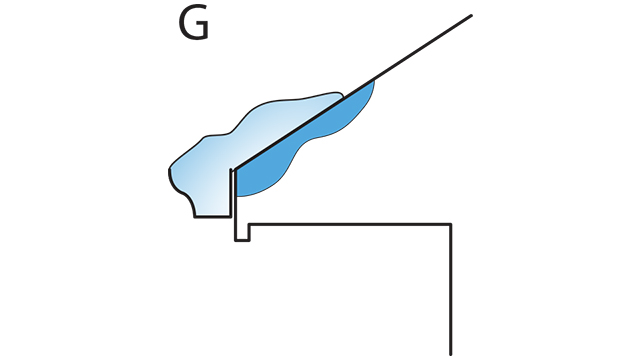

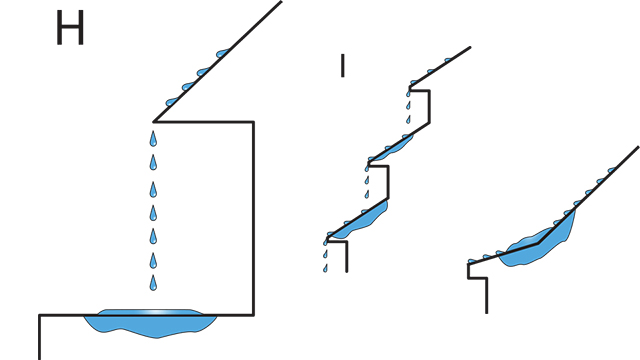

The best scenario for liquid water, once it is off a roof perimeter detail and headed downward, is directly to a designed grade. (See Image F-1.) If it comes in contact with the surface of the building’s exterior wall or lands on another construction detail, more work is to be done. (See Image D.)

Part II: Out of a construction detail

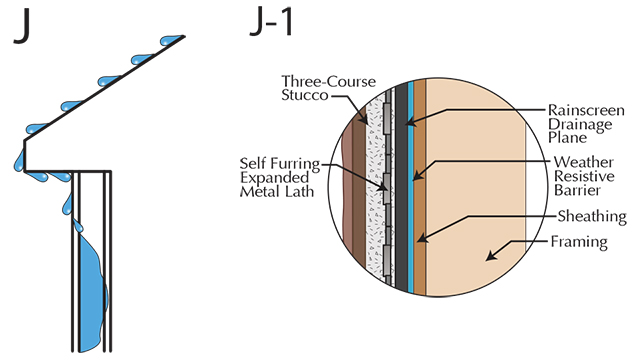

The amount of water entering a construction detail is certainly of concern. However, the amount of “time” that even a small amount of water is in a construction detail also is of concern. The extended time factor will allow moisture to absorb more deeply into the detail. Amount and time are negatives, because they extend the drying cycle – possibly even into the next wetting cycle – allowing the construction detail to be in a perpetually wet condition.This extended wet condition also may be subjected to a freeze-thaw cycling, compounding the problem. The amount of time that moisture is in contact with a construction detail is, in many cases, even more critical than the amount of moisture involved. It also can result in the much-publicized mold issue.

of” a construction detail is the law! (2009 IBC R703.12.1.)

Part III: Away from a construction detail

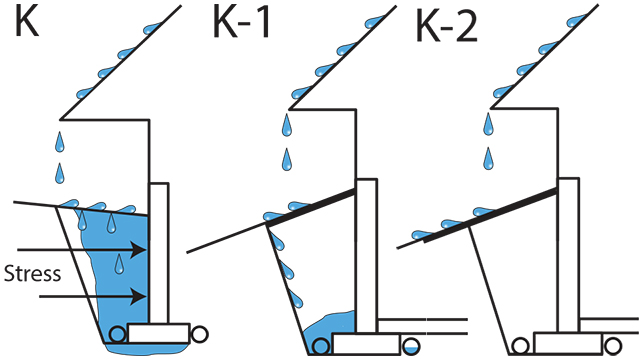

Once the liquid water is on the top surface of the surrounding grade, the third element of moisture management comes into play. We need to get the moisture that we have drained “off of” and “out of” the building, “away from” any and all construction details. Building sites must have a designed drainage plan. This drainage plan should be in place from the earliest stages of the planning phase; it should be rigorously maintained during the construction phase; and it should be continued throughout the building’s useful existence.Unfortunately, this is one of the most neglected aspects of good moisture management. If neglected, dire consequences may occur, since critical structural components of a building such as basement walls and footings, and their supporting soils, may be compromised. (See Image K.)

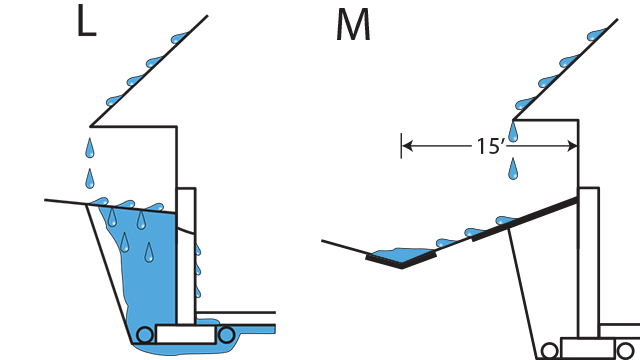

Landscaping, both hard and soft, that is immediately adjacent to buildings must be designed to compensate for fill disturbed by foundation excavation. (See Images K-1 & K-2.) If this runoff water needs to be diverted around dwellings, the pathway swale needs to be a minimum of 15 feet away from dwelling and, preferably, hard surfaced. (See Image M.) Excessive moisture will also over-stress the moisture-resistant coatings and drain tile systems that should be a part of below-grade construction details. (See Image L.)

If the ambient temperature in the below-grade construction details cannot keep basement walls and floors warmed, and if they are constantly in a cool condition, chances are that surface temperatures of these foundation components may be at or below the dew point, and condensation will occur. When water vapor condenses on a surface, or on other air particles, liquid water droplets form. This can and often does create a “wet basement.”

By now, it should be apparent that, by not complying with the “away from” part of the rule of good moisture management, really bad things can and will happen. Designing and maintaining a good drainage plan for a construction site is not easy, but it is well worth it. A construction site with a designed and maintained drainage plan is more efficient for everyone involved. A site that is allowed to turn into a “swamp” will regularly impact the site, including the soils and the fill surrounding the building foundation, and that may have both short-term and long-term negative consequences.

Conclusion

When it comes to managing moisture, it should be obvious that there are direct connections among all moisture management conditions and components. John Donne wrote, “No man is an island, entire of itself.”The same thing holds true for any construction component or detail. Very few, if any, features or factors of a construction project stand alone. A holistic relationship exists, and the improper treatment or neglect of any one component will imperil the rest.

Originally published in Masonry magazine.

About the Author

John Koester is CEO Masonry Technology, Inc. He can be contacted at johnk@mtidry.com.